‘Does no other profession occur to you, which a young man of your figure and address could take up easily, and see the world to advantage in?’ asked the manager.

‘No,’ said Nicholas, shaking his head.

‘Why, then, I’ll tell you one,’ said Mr Crummles, throwing his pipe into the fire, and raising his voice. ‘The stage.’

‘The stage!’ cried Nicholas, in a voice almost as loud.

‘The theatrical profession,’ said Mr Vincent Crummles.

Charles Dickens, Nicholas Nickleby

|

| Photo by EP |

In celebration of the bicentenary of Dickens’s birth, just past, I reproduce here the essay I wrote for the programme of Nicholas Nickleby, nearly thirty-two years ago, on the subject of Dickens’s theatre.

Those actors who find they don’t have to draw lines on their faces anymore, but perhaps have to cover them up, are probably old enough to feel that they’ve acted with Dickens’s Mr and Mrs Vincent Crummles. I certainly did; it was at the Arcadia Theatre, Lowestoft or the Hippodrome, Stockton – I’d better not say which – twenty-two years ago. I was offered four pounds. The Equity minimum was seven pounds ten, so as a member of Equity, I said I couldn’t possibly act for less than six. I was sacked after two weeks on account of my enormous salary and the tiny houses – though the fireman said, bless him, ‘You’re the one I’d ’ave thought ’e’d ’ave kept.’

Actually it’s over a hundred and forty years since the original Vincent Crummles met Nicholas on the road to Portsmouth but, despite the vast changes, he remains delightfully recognizable, even though the country manager he epitomizes has been almost completely replaced by the university graduate or more likely a co-operative of graduates running a small touring ‘community theatre’ on hard graft, social or ideological commitment and persuasive talk at the Arts Council.

The great bulk of the early and mid-Victorian theatre repertoire remains unrevived and possibly unrevivable; only a few actors’ names are remembered, but somehow the afterglow lingers, and for many of us the notion of theatre and theatricality in the best and worst senses has everything to do with what was on the week Nicholas Nickleby arrived in London. This afterglow is fanned by the sight of plush and gold leaf, our memories of toy theatres and our first pantomime visit.

At two of the many glorious extremes of the theatre of the late 1830s were the Theatre Royal Covent Garden and Richardson’s travelling booth.

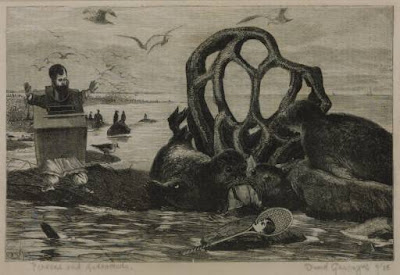

|

| Richardson’s booth depicted by Thomas Rowlandson |

|

Kean as Brutus.

By James Northcote (1819). NPG |

The great Edmund kean who died at thirty-five or so, five years before Nicholas arrived on the scene, had a career that took in both the gaudy canvas booth as a strolling player and the neo-classical building in Covent Garden based on the Temple of Minerva on the Acropolis. This particular Covent Garden Theatre Royal, today’s predecessor, was built and opened in a year – about as a long as it would take a theatre company now to plan for and acquire a travelling canvas booth.

The strollers had their own slang. ‘We think it must have originated from Italians who went about doing pantomimes’, one of them told Henry Mayhew.

The Italian influence from the Commedia dell’Arte was also obvious at the temple of Minerva in Bow Street and at the other Royal Patent Theatre round the corner in Drury Lane, though these two houses (together with the Theatre Royal, Haymarket in the summer months only) were the only theatres in London allowed by law to perform Shakespeare and the ‘legitimate’ drama. They found it expedient to mix in a generous amount of Pantomime, Harlequinade and Ballet, and as all the textbooks say, our traditional English Pantomime came from the Commedia dell’Arte via the Paris fairground booths. Even animal acts were to be seen at Drury Lane and Macready, leading actor at Covent Garden, was appalled that the young Queen Victoria had gone backstage to see the lions ‘again’! Crummles could hardly be blamed for introducing his donkey. But strangely enough the Strollers would act Shakespeare when doing ‘private business’ outside the fairs ‘ ‘then we go as near as memory will let us. We only do the outline of the story and gag it up.’

|

Macready as Henry IV.

By John Jackson (1821). NPG |

But one must be careful not to confuse Mr Crummles’s line with the fit-up booth business. He would have been as aware of his precise placing in the system of layers as anyone else in any other walk of life. Macready was keenly aware of his position at the head of the acting profesion, jealously watching the exploits of Edmund Kean’s son Charles at Drury Lane (‘that imposter’) and bitter that because of his station as an actor he could not really be regarded as a gentleman and would certainly not be received at Court, though he performed regularly to the command of Victoria and had the honour of meeting her in her box and ‘lighting her down’ to the Royal exit. Perhaps it was some comfort that from his well-lit position centre stage one night he directed the following lines as King Lear at the Queen:

Poor naked wretches, whereso’er you are,

That bide the pelting of this pitiless storm,

How shall your houseless heads and unfed sides,

Your loop’d and window’d raggedness, defend you

From seasons such as these? O, I have ta’en

Too little care of this! Take physic, pomp;

Expose thyself to feel what wretches feel,

That thou mayst shake the superflux to them,

And show the heavens more just.

He was being paid more than the Prime Minister at the time.

The theatre was thought to be at a low ebb around 1838, but Dickens couldn’t stay away from it. Earlier in the century Jane Austen, who must surely have been a sensitive and discerning theatregoer, saw Edmund Kean as Shylock and wrote of the ‘most perfect’ acting she had seen. From the point of view of dramatic literature it has left us comparatively little – but so much else has come down of the tradition – even of the ephemera of the stage which theatre people still measure themselves by, fight against, and dream about with nostalgia. People say that Dickens invented ‘Christmas’. By the same token, did the Georgians and the Victorians between them invent ‘The Theatre’?

______________________________

A taste of the Victorian fairground and of Victorian Shakespeare:

|

Beerbohm Tree as Mark Antony.

By Charles Buchel. V&A |

And, finally, a compilation of some of Emily’s and my scenes in Nickleby, together and apart:

Postscript

If you missed Edward’s readings from

Little Dorrit as part of the BBC News feature on Dickens’s anniversary last Tuesday, click

here.

Part 2 of Edward’s Dickensian Blog will follow shortly.

K.R.