As flies to wanton boys ...

KING LEAR

My voter apathy was such that I didn’t respond to British Actors’ Equity’s invitation to the Peacock Theatre to show solidarity with the Belarus Free Theatre, at home forbidden to act in anything but the official language of Russian, always under threat of prosecution and worse and reduced to giving fugitive performances in private apartments. But I did fork out the top price of £35 to see them act King Lear at the Globe on Bankside. I have no idea whether their high profile champions, Stoppard, Spacey et al, were there too, because the only centre seats left on the day were in the top balcony, a star- and celebrity-free zone.

Grunge was the style: the portions of the kingdom handfuls of earth which the young Lear shovelled into the held-out skirts of his daughters, who had sung their love in Eurovision mode accompanied by the Fool on the piano. A dramatic chance for Cordelia’s ‘nothing’ we thought until we noticed her singing along with them. For reasons that were not clear she too sang solo but gained nil point.

The French King was a doddering grotesque, from an expressionist cabaret, but then Gloucester was a wheelchair-bound incontinent – the business of his arc of urine being captured with difficulty by his bastard son in an enamel bed pan (some laughter from the groundlings for this inexplicable dumb show) accompanied the father considering the faked evidence against the legitimate Edgar who eventually appeared with a friend, both helpless with weed-induced mirth. There was little sign of the longer speeches; they whizzed by, cut and at conversation pitch. What happened to the curse, ‘Blow winds’, ‘Poor naked wretches’, or any of the speeches in the storm? But then the main protagonist here was the blue tarpaulin, waved about by an insistent singing chorus who chucked a plastic bowl of water over Lear. Edgar, meanwhile, had disguised himself as Poor Tom by smearing himself with his own excrement; everybody in the storm took off their clothes in sympathy with his nakedness. I decided this what not King Lear by any stretch of the imagination and exercised my freedom to leave. I don’t know how these actors got out of the authoritarian Belarus, but were I a critic I would find it hard to attribute praise to them that might lend them credibility when they get back.

The irony for me was that the production bore all the hallmarks of the authoritarian eastern European director. One remembers tales of Lubimov flashing his torch from the back of the auditorium to warn the actors that they were too slow, and I vividly remember him in a television documentary demonstrating a piece of business to Ron Cook which by that time I had already seen Cook slavishly reproduce in his performance in Crime and Punishment. I also remember Michael Billington, having been captivated by Lubimov’s Hamlet in Moscow, being disappointed when he saw the same production in English with English actors and realizing how cut about and diminished the play really was under all the pyrotechnics.

I suppose it’s easy in a liberal society to carp when theatre companies don’t aspire to Shakespeare’s greatness but appear instead to be using his material to hang theatrical effects on. This clearly works for some people because one online critic thought the Belarus Free Theatre had given us one of the greatest Lears London had ever seen and that the production comprised one coup de théâtre after another. An example of this was the scene in which Lear confronts his two daughters and they are already conspiring against him and stripping him of his followers. Shakespeare has him humiliatingly caught between their wiles. The cruel domestic politics of this were here replaced by kinetic capers, the daughters embracing Lear around the neck so that he could spin them round in an accelerating turn that threatened to have them parallel to the ground. The business told us nothing of Shakespeare’s scene. These so-called coups de théâtre were really radical replacements and, in this case, the coup was a mere spin-off.

|

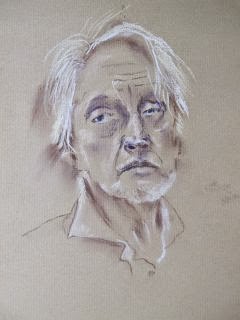

| Photo by Simon Kane |

|

| Photo by EP |

Meanwhile, back in the suburbs, the weather has brought out the best in wild and civilized West Hampstead. A fox takes his ease just over our garden fence and a couple watch the distant white-flannelled cricketers on UCL’s playing fields.

|

| Photo by EP Photo by EP

Postscript

My friend Kathleen Riley, who manages to be at my elbow and in Sydney at the same time, is actually in London this month and I had the pleasure of attending the Platform to launch her book The Astaires: Fred and Adele in the National’s Lyttelton Theatre, which packed the stalls and spilled over into the circle. Kathleen, aided and abetted by Ava Astaire McKenzie, Fred’s daughter (looking remarkably like her father) and choreographer Matthew Bourne, with interlocutor Al Senter, held us all spellbound. But I confess that, although the long queue for signed copies afterwards was equally impressive, I enjoyed a more thinly attended event at our local bookshop in West End Lane where she and I, dressed to the nines for the occasion, held a heart to heart in public about the glories of her book.

The Astaires is written with all the rigour you’d expect from a classical scholar and all the flair you have no right to expect to be combined with the whiff of Broadway and the West End of the interwar years. It seems Kathleen recreates the entire era whilst sitting next to an open trunk containing two pairs of famous dancing shoes.

|