Beautiful as the horses of Hippolytus

Carven on some antique frieze.

Frederic Manning, ‘Transport’, 1917

My Blog this weekend is a film by Kathleen

with her accompanying introduction, appropriate to Remembrance Sunday. EP

|

| A Trojan four-horse chariot, eastern frieze, Siphnian Treasury, Delphi |

In January this year I gave a talk at the

Sydney Latin Summer School on the First World War Poets and their use of

classical mythology. To accompany this I put together a short slideshow of

images taken from Sidney Nolan’s Gallipoli series. Edward very kindly provided

the voice-over, a beautiful, spellbinding reading of Patrick Shaw-Stewart’s

poem ‘I saw a man this morning’. The poem was written on a blank page in Shaw-Stewart’s copy

of Housman’s A Shropshire Lad and

discovered after his death. To

mark Remembrance Sunday, we thought we’d give the film a wider ‘screening’.

But first, to put the words and images in

context …

The

disastrous Gallipoli campaign took place between 25 April 1915 and 9 January

1916; its aim had been to seize control of the Dardanelles straits from the

Ottoman Empire, to capture Constantinople, and open a Black Sea supply route to

Russia. An exact figure for the casualties at Gallipoli does not exist, but, to

give you some idea of their scale: of the Australian troops, more than 8,700

were killed and more than twice that number wounded, at a time when Australia’s

population was fewer than five million. New Zealand, with a population just

over a million, lost 2,721 troops.

|

Gaba Tepe (Anzac), the spot where the Australians landed upon

the Gallipoli Peninsula. Photo: Bettmann/Corbis |

The

location of the Gallipoli peninsula just across the Hellespont from the

traditional site of Troy, the site excavated by Heinrich Schliemann only forty

years earlier, carried such obvious, inescapable resonance with Homer; the

British and ANZAC troops were literally walking in the footsteps of Hector and

Achilles. With this tangible link with ancient tradition embedded in the very

topography of the new fighting front, it was impossible not to think of the Iliad. En route to Gallipoli, Rupert

Brooke promised to recite Sappho and Homer through the Cyclades and ‘the winds

of history will follow us all the way.’ On 23 April 1915, two days before the

fateful landing at Cape Helles and Ari Burnu, he died of sepsis from an

infected mosquito bite, in a French hospital ship moored in a bay off the

island of Skyros. Among the scribbled fragments found in a notebook he kept on

that last voyage were these lines:

They say Achilles

in the darkness stirred

And Priam and his

fifty sons

Wake all amazed,

and hear the guns

And shake for Troy again.

|

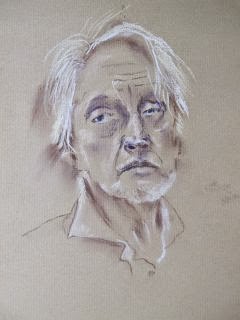

Patrick Shaw-Stewart

Image: Balliol College, Oxford |

Sailing on

the same ship as Brooke was Patrick Shaw-Stewart, a brilliant classical scholar from Eton and Balliol. Three months into the campaign, he composed a

very different poem in contemplation and anticipation of his Homeric inheritance,

which began ‘I saw a man this morning/Who did not wish

to die …’.

For most of

the poem, he aligns himself with the figure of Achilles and the hero’s rather

bleak dilemma – the exchange of long life for posthumous glory. In the final

stanza, however, it is as Achilles’ slain and unprotected comrade Patroclus

that Shaw-Stewart imagines himself. The Achilles whom he now calls upon is the

vengeful, flame-encircled epiphany standing between the Achaean wall and ditch,

dreadful in his divinity and his grief, thrice issuing a piercing brazen cry

and putting the Trojans to rout. This final stanza highlights the uncloseable

distance between Ilion and Gallipoli; the flame-capped epiphany is the stuff of

myth, an unattainable fiction which only emphasizes the immediacy and solitude

of the modern soldier’s reality and his reflections upon that reality.

Shaw-Stewart survived Gallipoli only to be killed in

action in France at the end of 1917. He was twenty-nine.

In 1955, inspired by his reading of Robert Graves’s The Greek Myths

and Homer’s Iliad, Australian artist Sidney Nolan began to work on a

Trojan War series. It was the novelist George Johnston who gave him the idea of

looking instead at the Anzacs as a modern reworking of the classical story. The

Nolans would spend a few months staying with the Johnstons on the Greek island

of Hydra in 1956. On the nearby island of Spetsae, another Australian, Alan

Moorehead (now buried in West Hampstead Cemetery), was completing what would

become his best-selling book on the Gallipoli campaign. At Johnston’s urging,

Nolan had read Moorehead’s New Yorker article which discussed the

geographical proximity of Gallipoli and Troy and the similarities between the

two campaigns.

|

| Sidney Nolan, ‘Gallipoli Riders’ |

|

| Sidney Nolan, ‘Gallipoli Man’ |

Nolan’s own research led him to the archaeological museum in Athens,

where he became absorbed by classical sculpture and the depiction of ancient

Greek warriors on vases. Around this time he also paid a brief visit to

Gallipoli and the site of ancient Troy. His reading of classical Greek

literature inspired his depiction of Australian soldiers as ‘reincarnations of

the ancient Trojan heroes of mythical times.’ His paintings and drawings of the

Australians on Gallipoli recall the vase images of Greek heroes fighting naked

and without their armour. They also recall novelist Compton Mackenzie’s famous

description of the Anzacs’ classical beauty:

Their

beauty, for it really was heroic, should have been celebrated in hexameters not

headlines. As a child I used to pore for hours over those illustrations of

Flaxman for Homer and Virgil which simulated the effect of ancient pottery.

There was not one of those glorious young men I saw that day who might not

himself have been Ajax or Diomed, Hector or Achilles. Their almost complete

nudity, their tallness, and majestic simplicity of line, their rose-brown flesh

burnt by the sun and purged of all grossness by the ordeal through which they

were passing, all these united to create something as near to absolute beauty

as I shall hope ever to see in this world.

In spite of their classical sources, however, Nolan’s soldiers are not

larger-than-life beings, but, instead, ordinary, anonymous figurines buffeted

by the forces of destiny.

Note: The

title of our film, ‘Arma virumque cano’ is taken from the very first line of

Virgil’s Aeneid (‘Of arms and the man I sing’). It was a Latin tag used

by War Poets such as Wilfred Owen to expose jingoism for what it was and to

reveal the disquieting ambivalence intrinsic to poems such as the Iliad and

the Aeneid. Bernard Shaw used the phrase too of course!

Postscript

Be sure to check Edward’s

News blog for the latest news, including an exciting announcement about a soon-to-be-released audio edition of

Slim Chances.